Few films so masterfully blur the lines between dream and waking life as Field of Dreams (1989), a story that touches deep psychological chords about loss, longing, and legacy. Often dismissed as merely a sentimental baseball movie, it is in fact a poignant meditation on generational healing, spiritual calling, and the often unseen sacrifices involved in following one’s inner voice. Through Ray Kinsella’s mystical journey from skeptical farmer to faithful dreamer, the film invites viewers to confront their own buried grief, familial estrangements, and internalized narratives about purpose. In this analysis, we will explore the psychological themes of intuitive calling, father hunger, reparative imagination, and the archetypal guides who assist us along the way—supported by relevant academic literature.

Intuitive Callings and the Leap of Faith

Ray’s journey begins with an unexplainable voice—“If you build it, he will come”—a calling that defies logic and challenges the expectations of everyone around him. This inner directive can be viewed as an intuitive awakening, which some psychologists understand as a form of inner wisdom arising when individuals begin to realign with a deeper truth about their life path (Hill, 2001). Ray’s resistance is gradual, but the unwavering support of his wife Annie and his daughter Karen reinforces the importance of having emotionally secure attachments when one risks social ridicule to pursue a path guided by inner vision rather than societal norms. In many ways, Ray is undergoing a spiritual emergence, a psychological transformation that may at first mimic symptoms of delusion or instability, yet actually reflects a deeper realignment with one’s purpose (Lukoff et al., 1998). His decision to plow over his corn to build a baseball field—met with ridicule from neighbors—symbolizes the personal cost of trusting one’s call, especially when that call threatens financial ruin and social alienation.

Peak Scene: The Plowing of the Corn

One of the most memorable moments of the film occurs early in a scene where Ray, holding his daughter on his lap, blissfully plows down his crop to build the field. This is a moment of sacred rebellion, where his act of creation is done not with certainty of outcome but with clarity of intention. The scene resonates deeply with anyone who has taken a leap toward a nontraditional life path, especially in defiance of intergenerational expectations or economic logic. Ray, narrating stories about Shoeless Joe Jackson as he works, shows the fusion of myth and memory, where storytelling becomes a means of meaning-making. This moment echoes the Jungian idea that the soul is nourished not by conformity, but by symbolic acts that reconnect us to our personal myth (Jung, 1964).

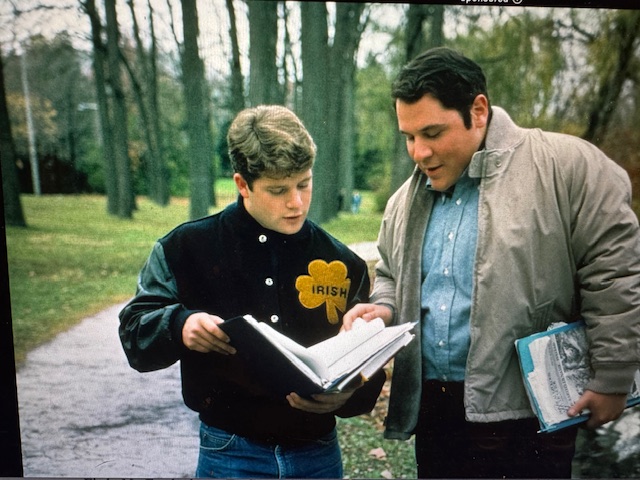

Terrance and Archie: Archetypal Guides and Second Chances

The journey deepens with the arrival of Terrance Mann and Archie “Moonlight” Graham, who serve as powerful archetypal figures representing the inner artist and the unlived life, respectively. Terrance, a reclusive author disillusioned by fame and the state of the world, is drawn back into joy, purpose, and childlike wonder through his time on the field. His transformation is symbolic of the reawakening that occurs when one reconnects to passion and service. Archie, who appears as both a young ballplayer and later as the seasoned Dr. Graham, embodies the idea that a meaningful life may not look the way we imagined it—but its fulfillment can still come full circle. When he sacrifices his chance to stay in the game in order to save Ray’s daughter, his act reflects the individuation process Jung described, where one must integrate youthful desires with mature wisdom in order to fully actualize the Self.

These characters help Ray—like a hero in a myth—move through the liminal space between the known world and the unknown. Terrance’s decision to walk into the cornfield with the other players represents a transcendence of worldly concerns, while Ray remains behind to complete his final reconciliation. In clinical terms, they can be viewed as transitional figures in a client’s therapeutic process—mentors or memories that assist in bridging the past with the present and guide the soul toward completion.

The Longing for the Father and the Archetype of Repair

At its core, Field of Dreams is about repairing the rupture between father and son. Ray’s unspoken guilt about refusing a final game of catch with his father John forms the emotional undercurrent of the entire narrative. Psychologist James Hollis (2005) notes that unresolved “father hunger” often drives men to undertake unconscious quests in adulthood, attempting to reconcile the loss of paternal connection through work, relationships, or symbolic action. In Ray’s case, this yearning manifests as a literal resurrection of his father’s youth. The line “ease his pain” is initially misinterpreted as a call to help others, but ultimately, it refers to Ray’s own emotional wound—the absence of closure with his father. By building the field and engaging with figures from his father’s era, Ray is unknowingly creating the conditions for that healing encounter to take place.

The final catch between Ray and his father is not merely nostalgic—it is an enactment of reparative imagination, a technique used in trauma therapy in which individuals are guided to mentally reconstruct missed or painful moments with more healing outcomes (Brown & Elliott, 2016). That one word—“Dad”—spoken with reverence and vulnerability, undoes a lifetime of regret and restores the fractured bond. The film’s brilliance lies in its ability to hold this act of fantasy not as escapism but as sacred truth. In that moment, heaven is not another place, but the ability to be fully present with a loved one long lost.

Conclusion

Field of Dreams is more than a story about baseball; it is a mythic exploration of intuition, loss, forgiveness, and the healing power of symbolic action. Through Ray Kinsella’s mysterious journey, the film invites us to ask what parts of ourselves we’ve abandoned, what voices we’ve ignored, and what relationships we long to repair. Clinically, it speaks to the power of inner callings, the necessity of grieving generational wounds, and the importance of imagination in therapeutic healing. As the lights go on and father and son toss a ball in the twilight, we are reminded that the field we build with faith may become the very place where redemption finds us.

Mike Bribeaux, LMFT, PhD Candidate in Integral Health

References

Brown, N., & Elliott, R. (2016). Reparative imagination in therapeutic practice: Healing past attachment trauma. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 46(4), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-016-9330-7

Hill, L. (2001). Dreams and inner guidance: Understanding your dreams to guide you through life’s transitions. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 41(4), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167801414004

Hollis, J. (2005). Under Saturn’s shadow: The wounding and healing of men. Inner City Books.

Lukoff, D., Lu, F., & Turner, R. (1998). From spiritual emergency to spiritual problem: The transpersonal roots of the new DSM-IV category. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 38(2), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678980382003